The last second went by; the year was over. There was no ceremony. There hadn’t been last year, it dimly recalled. It hadn’t arrived with the understanding of what it all meant. Now there was the new year, stumbled in, flush with promise; and it, the old year, was expected to go—where? It had never thought to ask. The new year wouldn’t know. It didn’t know anything. That was how it was.

But it’s not fair, the old year thought. I’d only just arrived. If I’d known that it would be this way, I would never have come in the first place.

Even as it had these thoughts, it knew that they were pointless. Whoever was in charge of this changing of the years did not leave them any options. It was only now, when its duties had been discharged, that it felt any consciousness of itself at all.

In the world of time, seconds ticked and ticked and ticked; nobody seemed to notice. People were popping champagne, kissing each other, crying. The old year could see their resolutions for the new year written on their faces in bright bold colors that were—already—fading to nothing.

The new year was absorbing the experiences of the world moment by moment. That, the old year could remember—the overwhelmingness of it all. The time-bound were lucky, it thought. They could do this over and over, until they got good at it. For the old year, there had only been a supersaturation of instants, and then—release.

“Look,” it said to the new year. “Where do I go?”

The new year could not hear.

At first, the old year tried taking up residence in the homes of the elderly, but their minds were turned toward an even further past, and that was too depressing. Instead, the old year began to go bars. It would perch on the shoulders of men drinking alone, women drinking with their friends, just to hear them drunkenly reminiscence. “You’re too hung up on the past,” it’d hear them say. “That was last year.”

The old year wasn’t too proud to want attention. It would have been happy to admit, if there had been anybody to admit this to, that it hung around these places just for the thrill of knowing it was recollected. Instead, it would just follow the occasional promising barfly back home, where it could at least feel remembered by how miserable the person was if by nothing else.

Surely (the old year thought, as it floated after a crying young woman who had sent several alternately pleading and enraged text messages to somebody labeled “DOUCHEBAG ASSHOLE” in her contacts) this slapdash haunting was not how things were meant to go. The “time-bound,” it had called all that lived and died under its reign. Now the old year seemed to be time-bound, too. Instead of experiencing every instant, it simply drifted from place to place. What it had expected to happen after it had been superseded it could not say, but it had expected—something. It had learned that much from watching people day after day: one thing follows another. If it had possessed no consciousness of its own eventual end until the new year appeared, nevertheless—there was supposed to be something. An afterlife for aftertime. Yet there was nowhere to go.

The old year wrapped itself around the crying young woman, who had by now arrived home to her inevitably miserable and cluttered apartment and was texting somebody named “Mel.” It’s like it won’t let me go, she typed into the phone. Everything that happened. I just want to move on, but I can’t. Encouraged by this result, the old year wrapped itself around the woman a little tighter.

“Do you think that’s fair?” said a voice the old year didn’t recognize, but knew somehow. There in a corner of the crying young woman’s bedroom, it saw another year, much older, sitting on her radiator.1 “I was wondering when I’d find you,” it went on. “I like to see the years in, you know, but sometimes you’re hard to run to ground. But you should really leave her alone. She’s not going to forget you that easily.”

“Where do we go?” the old year asked, now that there was finally somebody to ask at all.

“We don’t go anywhere,” said the older year. “We’re the past.”

“Who are you?” the old year asked.

“Oh,” said the older year. “I’m really a lot older than you could possibly imagine. I’m 1872. But that was when they built this place. It was nice then, you know. Not so much now.”

“What do we do?” the old year asked, conscious of a certain basic quality in its questions.

“We don’t do anything,” said 1872. “We never did, you know. They do things.”

The old year thought about it.

“I don’t think it’s fair,” said the old year. “Why can’t we be like them? Why can’t I get another shot at being a year? What if you could be a better 1872, if you got to do it again?” The old year looked around the bedroom. “Or why don’t we get to be them? There’s so much junk in here. I would clear it all out—”

“But you’re junk now,” said 1872, mildly, patiently, in the soft and well-worn tones of a year that had often had this conversation. “We’re all junk. That’s what it means to be the past.”

The old year didn’t have feet but if it had it would have stamped them. “What would you know?” it demanded. “You’re so old. You don’t know anything about how it is.”

“Yes, yes,” said 1872, getting up from the radiator. “I know, I know. You don’t need to go on. I’ve heard it before. 1991 was just the same. You’ll see. You know where to find me.”

After that, it saw the older years often. They would be curled up like cats on the ledges of buildings, hanging themselves hopefully over commemorative plaques, drifting around graveyards toward the entrances and exits they had once overseen. The most desperate cases hung about schools looking to see if they’d made it into a textbook. The old year promised itself it’d never become such a dreadful thing, a year desperate to be remembered. Hadn’t it contained within itself all of life and death? Who could forget such a year as it? Yet things got blurry all the time. There were more and more years and the old year began to fear that they weren’t all older. It could have spoken to them, of course, but it didn’t want to. There shouldn’t have been any other years. There should just have been itself, one perfect year, getting better and better.

It thought about 1872, sitting on the dusty radiator, all dusty itself and indistinct at the edges. The old year, since it had no solid body, couldn’t see itself or even use a mirror but it worried that if it could it would see that it, too, had begun to fade and fray, to blur. No, no. No. It couldn’t happen, wouldn’t happen. But there were so many years, and when the old year finally saw one so crisp and distinct it might have been stamped out by a press, it knew that it had become, by that time, a very old year.

It found itself once more in the houses of the old, but this time to be remembered in any sort of detail. It even—to its shame—snuck a peek at a textbook. There it found neither itself nor 1872, still the only year it had ever really spoken to. The old year wondered. Would there be a time nobody ever remembered it? What would happen then? It tried to go back to the building where it had met 1872, but it had been torn down. In its place stood something new, glinting glass and steel, expensive. The old year didn’t recognize anything anymore.

By now, some of the years had banded together into decades and centuries, becoming mish-mashed beings in which they could be only indistinctly discerned. The old year didn’t like the thought. In any case, banding together like that didn’t seem to help, it wasn’t like people remembered any better. On and on the years came, faster and faster, each one feeling shorter somehow than the last as the old year’s existence grew thinner and thinner. They fell like a blizzard all about it, encasing it, eroding it, as without even the ability to cry out in protest the old year was at last swallowed up by the great gullet of the anonymous past.

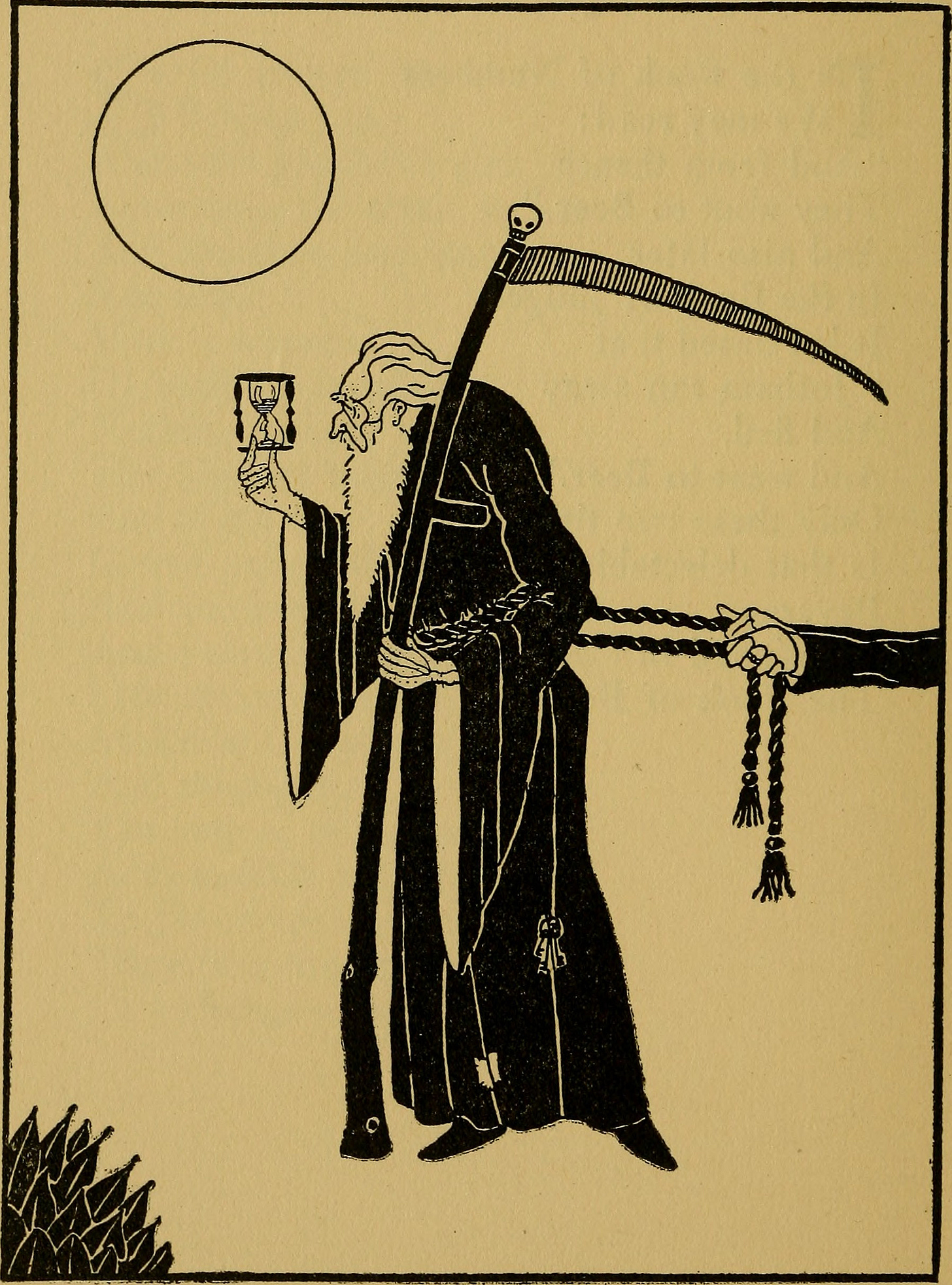

You might wonder, at this juncture, what a year looks like, since, after all, they don’t have hands or noses, but apparently they can sit on things if they choose to do so. If you could see a year, it would look like a snake that swam through the air: a smooth curling shape with a beginning and an end. But how years look to one another, nobody really knows.