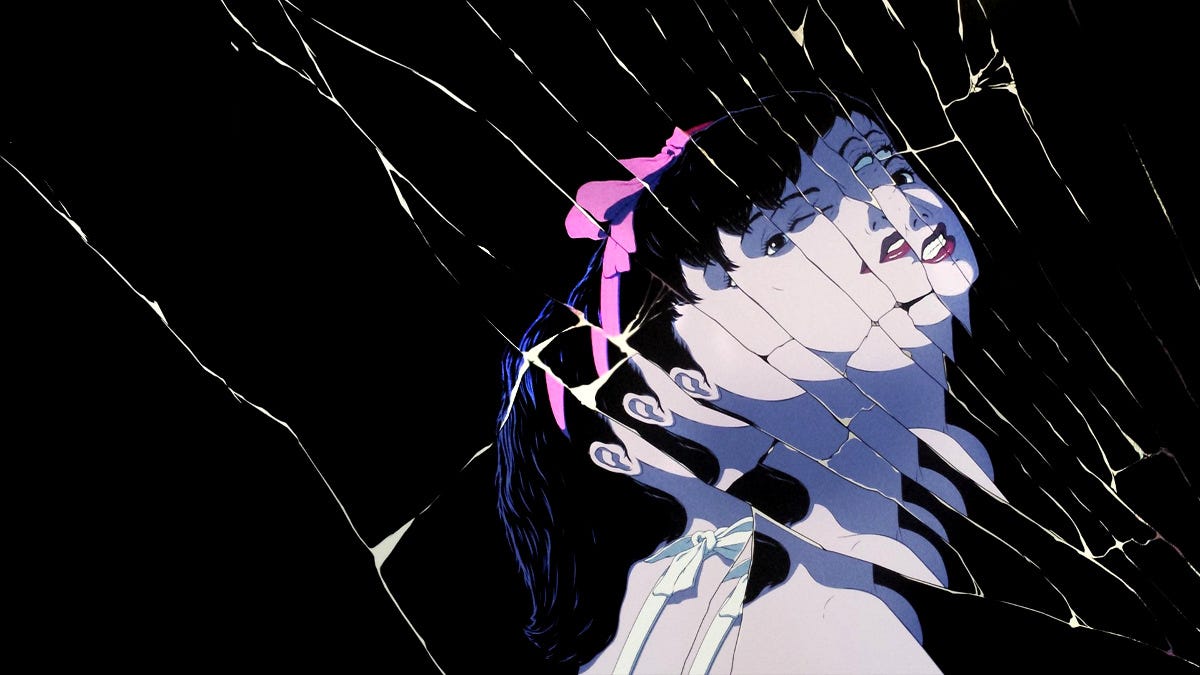

In Satoshi Kon’s Perfect Blue, pop idol Mima is ready to change her image: from innocent star to mature actress. It’s a decision that’s partly about money, partly about people-pleasing, but also, in a subtle but real way, about her own desires. There’s too much suffering entailed in becoming the actress she’s decided to be for her not to have chosen it herself. When we see her as a pop idol, she’s fine during the routines, but outside of them she is shy, afraid of disappointing her fans, unable to announce even her own departure.

It turns out, though, that she’s right to fear her fans. It doesn’t feel as if the singer for a not-especially-successful group should have enough obsessive fans for them to be a problem for her, but as she discovers, it only takes a few for stalkerish persistence to become actively frightening. Convinced the real Mima is being erased and slandered by an imposter, being made dirty and filthy by playing the parts she plays in dramas and in the press, her fans turn first to violent threats and then to real violence. At the receiving end, Mima can only say but I’m me, I’m really me, I’m the real me, I’m me to an uncomprehending and hate-filled audience.

As a pop idol, Mima is meant to be authentic—but in a fake way. She’s an approachable dream girl, innocent but not too innocent, cute and feminine while staying down-to-earth. She sings shallow, silly songs about love in a pink dress. It would be creepy if this were actually what she was like, if she were just a wide-eyed doll for other people to have feelings about, but of course this doll is just another role, it’s just meant to be invisible as such.

But as an actress, Mima gets to be fake in a way everybody knows is fake. She “betrays” her dedicated fans in two ways: by not staying the same person forever, and by revealing that that person wasn’t ever real. This shift is maybe most highlighted in a scene where she plays a character who is raped, and when the director yells “cut,” the man playing the rapist sheepishly apologizes to her. She’s fine, she assures him. This scene ends up dragging out so long that it becomes funny and then just becomes brutal: the director keeps yelling “cut” as Mima wails “no,” everybody keeps snapping back to normal, then the scene starts and she has to start screaming again.

Mima’s not as fine as she says, but she’s also okay: it is true that nothing has happened to her. Part of what Mima has to realize over the course of the movie is that her previous self wasn’t “real,” too, and that was why it was so comfortable for her. She begins to hallucinate it as another self: hostile, seemingly super-powered. Eventually it turns out this other self is real, sort of—a kind of creation of sheer rage and desperation from the people who wanted something else out of her.

Anyway, when I watched it, I texted a friend: if I were Taylor Swift I would watch this movie every night. Unlike Mima, Swift is a big deal. But like Mima, the existence of what you could call Tulpa Taylor is a problem for her. It is more of a problem for her, I think, than for other celebrities, not just because she is so famous, but because she sort of needs Tulpa Taylor, and, indeed, had a hand in creating her.

Some gossip that was breaking around the same time I was watching Perfect Blue: Taylor Swift (Pennsylvanian) ended her relationship of six years with Joe Alwyn (Englishman) and then apparently taken up with another Englishman (Matty Healy) in short succession.1 The Swift–Alwyn relationship was a public fact and, notoriously, very private. Pictures of them together are not common and when Alwyn was asked what his favorite Swift song was in an interview—a pretty easy softball, given that a number are purportedly about him—he didn’t give an answer.2 The only narrative that relationship has ever had is a closed door.

When Alwyn did not show up to any of her concerts on her current very big, incredibly sold-out Eras tour, it raised a few eyebrows, but not that many, because, again, they were very private. Nevertheless, People magazine put out a story rather clearly dictated by Swift’s PR team stressing that the couple was better than ever, and Alwyn wasn’t at the concerts because he was working… only to, a little over two weeks later, put out another PR-sourced story saying the couple had actually been broken up for a while, and that was why he didn’t attend anything. What’s interesting here, to me, is not that the stories contradict each other but that the second one admits the first one was never true. Why do it that way? The public narrative of a relationship that was solid because it was so private has been slowly replaced by one about a relationship that was so private because it was so fragile.

About Taylor Swift, the real person, I have few opinions, no knowledge, and not a lot of interest. If “real Taylor” showed up at my door for a cup of coffee maybe we’d get along, or maybe we’d have nothing to say to each other. I do not try to divine what this person is “really like.” How would I know? I don’t even know what I’m “really like.” In Taylor Swift, artist, on the other hand, I am very interested, a fan, and so on. But what I am also very interested in is the creation of Taylor Swift, persona and brand, which is built simultaneously on the assertions that what you’re seeing is real and what you’re seeing is fake.

I didn’t really get into Swift’s music until Red, and so mostly missed the period where she would leave encoded messages in her CD booklets about what this or that song is “really about,” though even then the encoded messages seem to have often just been another kind of coded message. But I take this practice to be both foundational to her image and a problem for the real person who creating the art and maintaining the brand. The idea that she leaves secret messages for her real fans is part of what helps her maintain her particular brand of public intimacy with her fanbase, but it also means any given Swift fan’s twitter page is like reading one of those numerology things that adds the numbers of Bible verses to predict the end of the world.3

The encoded message / Easter egg is also a way of reformulating tabloid scrutiny under a more harmless guise—like, it might sound kind of annoying to have details of your outfits scrutinized, but it’s probably better than having your fans constantly pestering you to know if you’re pregnant. If you are going to be under that much attention, why not make it kind of fun? Why not direct it yourself?

But it also means that Taylor Swift, artist, ends up overshadowed by the drive to figure out what any given song is “really about,” long after the coded messages have been dropped, a practice Taylor Swift (person? brand? artist?) has indicates annoys her:

When this album comes out, gossip blogs will scour the lyrics for the men they can attribute to each song, as if the inspiration for music is as simple and basic as a paternity test. There will be slideshows of photos backing up each incorrect theory.…

Let me say it again, louder for those in the back... We think we know someone, but the truth is that we only know the version of them that they have chosen to show us.

This brings me to what I find kind of interesting about the current project of Taylor Swift, brand, which is to try to introduce to her fans the idea that she sometimes lies. By “lying” I partly mean “her songs are fiction, because they are art”—they’re not diary pages or emotional stenography. Her real life and real emotions are her art’s raw material, but once it’s a song, it’s something else. Thus people feel kind of betrayed by the songs she wrote when she was, presumably, happily in love with her prior boyfriend, because now they feel fake. But feelings themselves can’t really be “fake” or “real,” they’re just states of mind. Similarly, people were (in the early days of the breakup, anyway) weirded out by the way Swift seemed to be able to go right on stage and sing all these old love songs without being upset. This says a lot about the feeling of intimacy she is able to generate in a stadium, but also, of course she can—she’s a professional.

But I also think there’s an element here which is that yeah, she will just lie, or not comment, or ignore you, if you are poking your nose into something that isn’t your business. It is basically impossible to figure out when exactly she and Joe got together or when they broke up, and—why shouldn’t it be? Who could possibly want to know? What reason could they have? The public narratives that surround celebrities and their relationships can shift on a dime. They are not really about facts, just about feelings—our feelings, not theirs.

People try to deal with becoming very, very famous very, very young in a lot of ways, many of them self-destructive, and one classic arc for women who start young in show business goes like this: underestimated teen idol, precocious favorite, acting out, public implosion, eventual comeback on a lower level, public awareness that maybe you got a raw deal, better luck next time. Swift did not go through this arc, and, at 33, she’s not going to. She had her “fall from grace” in 2016, but in a way so vague that I think if you tried to explain it to anybody not super tapped into entertainment news they wouldn’t have understood what was going on. To some extent it was a manufactured fall—not by Swift, but by a media where being the darling one day means being the devil the next.

Instead, Swift created an alter ego, as it were—also named Taylor Swift. A projection of herself that isn’t herself. When you watch a clip of her at a concert and she seems to be speaking straight to you, you’re in the presence of her particular way of constructing her own public image: all these people don’t know me, but you know me, because you know this isn’t the real me, which makes it the real me, because it isn’t, because…. Many people who write about Taylor Swift seem to think they’ve seen the act drop, so that they saw, at last, the real thing. “For a moment, she dropped her camera-sharp gaze and looked right at our faces,” Jia Tolentino wrote in a 2015 review of the 1989 tour for Jezebel. “A deep, rude boredom passed over her expression, like a cloud. Then she looked back up, cunning and perfect, the dip already forgotten. That’s the Swift that interests me.”

But that is the Swift that interests just about everybody, actually. The one who is looking right at you, the one that drops the act, and who is there everywhere in her music. It is this much subtler creation that I think of as the tulpa. Everybody knows that a performance is a performance, that an onstage smile is a mask. Harder to grasp that what’s under the mask is just another mask; that, for you, the person in the audience, it’s masks all the way down. I’m not saying she’s the only celebrity that does this or that it’s her special invention, just that the ouroboros of real and fake is how she manages to be as famous as she is without completely losing her mind.

In fact, Swift rather consistently draws attention to this aspect of her public persona, but it simply doesn’t matter when she’s looking at you. The opener for her current tour, “Miss Americana and the Heartbreak Prince,” means she arrives on the stage proclaiming: “you know I adore you, I'm crazier for you….” It’s you and me, that’s my whole world. Who could that “you” be but—you? Sure, you know the word “parasocial” and you know Taylor Swift isn’t your friend and does not know who you are. But these are things you know in your head, not your heart, which is telling you that all of this is for you, the only person in the world who really knows what it means.

Does Taylor Swift (person) conceive of herself in these distinct ways? I guess my general approach here is premised on the idea that I can’t actually answer that question.… But I think the answer is yes, because she pretty consistently duplicates herself in her music videos, even before reputation with its “old Taylor” and “new Taylor.” (See, for instance, “You Belong With Me.”) You could also look at her very early performances, like the “Should’ve Said No” performance where she sheds the hoodie and jeans to reveal the dress and the put-together look, then undoes the glamorous reveal by stepping into a rainfall. Or there are the little skits that go with many of the songs on Speak Now, which gives it, as a friend of mine put it, a summer camp feeling: here’s who everybody is for this song.

But things became more dramatic with and after reputation. In “…Ready For It?,” a cyborg (thus, fake, I guess) Taylor Swift destroys another cyborg Taylor Swift, in “Delicate” she manipulates her face like a puppet and then becomes invisible, in “Look What You Made Me Do,” she stands on a screaming, fighting pile of her own past selves. In “The Man”4 she’s a male version of herself (sort of…), in “Anti-Hero” she splits herself into three people, and so on. Alongside this you have other images: living in the fishbowl that is also a cut-away dollhouse (“Lavender Haze,” “Lover”), for instance, a dollhouse she apparently burns down in the Eras concert.

I think this is a good thing, incidentally. The embrace of being multiple works for her. It’s a different thing from playing with an alternate persona. All the Taylors are real Taylors. She is, as she is in “Anti-Hero,” the depressive song-writer, the larger-than-life star, and the perfectionist attention-seeking performer. She is the mean girl and she is the band nerd. She is an icon of pink pastel femininity and she’s The Man. These are all her. That’s how it goes. You are always seeing a real thing. But that is not the real thing. That, you—meaning you, me, anybody likely to be reading this—are never going to see.

I’m writing all this in advance of going to the Eras concert in a couple weeks, partly to put down some thoughts in advance, partly because the Eras stuff does feel like it’s meant to put a cap on something. It, too, has the Many Taylors, representing all her previous albums, trapped behind glass. I’ve long assumed her re-recording project will end with reputation and then her first album, Taylor Swift, back-to-back, to indicate the way she’s coming full circle. But what comes after that?

Maybe nothing. There’s a feeling, I think, that we’re headed toward a big finale, but there doesn’t really need to be one. She has her movie project, which is, I think, what she’s planning to have as the next act in her life when she’s aged out of pop music, though that aging out may not be as inevitable as she seemed to once think. She might just wrap up the tour and wrap up her re-recordings and then go back to just putting out albums.

One interesting thing about Perfect Blue is that Mima eventually does have a bloody, nasty struggle with her alternate persona, but it’s not to the death. The false Mima cannot tolerate the existence of the real Mima, but Mima herself, once she grasps the situation, can allow the false version of herself to live. And she does. Her pop idol self will live on in a diminished version of itself, smiling out of the mirror at those who only wanted to see her. The real person goes on to do the things that real people do: live a life, grow and change, suffer in the pursuit of her goals, and smile a smile that is, in the end, only for herself.

If you want to read the other Taylor Swift posts for some reason, they’re here.

I have never cared about her romantic relationships and do not intend to start now. I’m fine if you are Done With Taylor Swift because you hate her new boyfriend…but it just doesn’t interest me.

Another way of putting this is that Alwyn was always kept very, very far from Taylor Swift (brand), though he has been tangled up with Taylor Swift (artist) in somewhat confusing ways.

Though it should also be said that the people who seem most doggedly convinced of her “everything’s a code,” puppetmaster, controller of all persona, and who seem most convinced that they are the true interpreters of all these messages, aren’t her fans, but her haters—or at least this is my impression after spending some time reading the various threads about her new relationship in the gossip subreddit r/fauxmoi.

I’m not a big fan of “The Man”—it’s fine, but I like Taylor better when she’s just a winner—but it was her first music video that she directed herself and ever since I saw this observation that it visually quotes Polanski’s Repulsion I’ve been sort of obsessed with it. Like… what?

was listening to Red just as this newsletter popped into my email and finished reading it just as Taylor says “who’s Taylor Swift, anyway?” in “22”

As mostly an outsider to this world, I am surprised by the comment that fans are possibly expecting an imminent retirement or quasi-retirement. I assumed she was in it for the very long haul.