I try not to write cranky posts about the state of modern letters on here for a number of reasons, which I could (will) sum up thus:

These pieces tend to get a lot of attention, but people who come for that sort of thing mostly only like that sort of thing. That is, they do not want Evangelion, Taylor Swift, reviews of random books and movies, perfume, or dog pictures, they just want to hear about how everything sucks now. That’s their right, obviously, but a big uptick in attention followed by a big downtick can be destabilizing. And also I don’t think everything sucks now.

Any statement that is true of some part of a large category, like “people who write about arts, literature, and ‘ideas,’” will not be true of all of it. If it’s true of, let’s say, even a third of it, that would be significant, but one could also say (truthfully) that it is not true of the majority. “What are you talking about” is usually a reasonable response. However, I will try to make as clear as possible what I am talking about.

While I am on the record as being pro–naming names, I don’t really want to hold individuals up as examples if what I’m talking about seems like a creation of various incentives—i.e. what is bad is not that individual people are choosing to write this way (what way? read on…) but that they are not choosing to do so, they do it automatically.

So having gotten that harrumph harrumph out of the way, let’s continue.

Much “culture writing” is bad. On Substack, in magazines, in books, wherever. (However, I’m going to leave Substack out of it for now.) “Culture writing” is a nebulous category that includes not only the traditional book or film review but the celebrity profile, a thinkpiece about a tweet you read, going long on The Real Housewives of Middle Earth, a denunciation of a trend, a Lacanian analysis of Addison Rae’s “Diet Pepsi,” or the kind of “para academic” writing that you find at (for instance) The Los Angeles Review of Books. All of this is “culture writing.” So is writing about fine art, ballet, the theater, or an observational bit of memoir, that thing where you look out the window see a man wearing a hat and write “HATS ARE BACK: WHAT IT MEANS,” etc.

The pieces I am going to criticize are not bad because they are insincerely positive or insincerely negative. They might be, sure, but I’m not concerned with that right now. They are not dedicated to propping up some sort of “elite” consensus about things (or falsely posturing outside it). They are bad because they’re written so defensively they manage to say very little. I am going to make up a pastiche here to show what I mean.

This paragraph+ is from a fake book we will call All Horned Up, a cultural history of the unicorn. All Horned Up is what we call “trade” non-fiction, that is, it is for normal people and not people who professionalize in the study of unicorns. Here are our paragraphs, taken from somewhere in its introduction:

From Lisa Frank to tapestries woven in the Netherlands, the unicorn has long held a fascination for little girls and adult women alike. “The unicorn, with its twin symbols of virgin and phallus,” wrote writer J.F. Christ in his book The Once and Future Unicorn, “represents what all girls subconsciously long for yet cannot possess: purity and power.” Standing in the Cloisters Museum, there at the uttermost tip of Manhattan, and looking at the Unicorn Tapestries myself for the very first time, I found myself thinking, too, that maybe this was what all girls wanted: a powerful creature to lay its head, just once, in your specially chosen lap.

Culture matters. Some critics have maintained that unicorns instill in girls a detachment from reality at an early age. In a longitudinal survey conducted of girls who had owned unicorn dolls from ages seven to twelve over thirty years, the sociologist Jenn Smith found that girls who own unicorn dolls were more likely to have eating disorders and less likely to do well in math. But they were also more likely to go on to successful careers in corporate America. You can’t make unicorns simple. Ask any girl.

So (you ask) what makes this fake paragraph+ I wrote to be bad on purpose… bad? There’s the fake historicizing (“from Lisa Frank…”) with its cute bounce from low to high, the pointless use of citing another author here to state a pretty obvious thought, and the retreat into narrativizing subjectivity. This subject matters because of this fake reason; this opinion isn’t mine, it’s this other guy’s; I am just reporting the stream of my own thoughts, not making a claim; by the way, here’s a study.…

The person who wrote this paragraph, if they existed, would know how to use JStor. They would know the right people to indicate that you know if you’re going to cover this subject. They would perhaps interview ten different unicorn enthusiasts they got by putting out an open call on social media. There are an array of buttons that this paragraph carefully pushes. But it’s just noise. What is being communicated here about unicorns, exactly? Nothing. It looks like it’s good writing—I have no real issue with a sweeping declaration, a quote, and a retreat into the first person—but it isn’t good writing, because these things don’t inform. It’s timid writing.

Now, OK—I made this paragraph up. It isn’t real. It is almost a literal straw man. The reason I did that is because anybody who is writing like this has been trained to do it—told over and over, essentially, that you need to make all these gestures or you won’t look like you know what you’re talking about, that you need to stick nonsense phrases like “the writer So And So wrote in his book” in or you’ll confuse people. But here’s a real paragraph+, with my underlining:

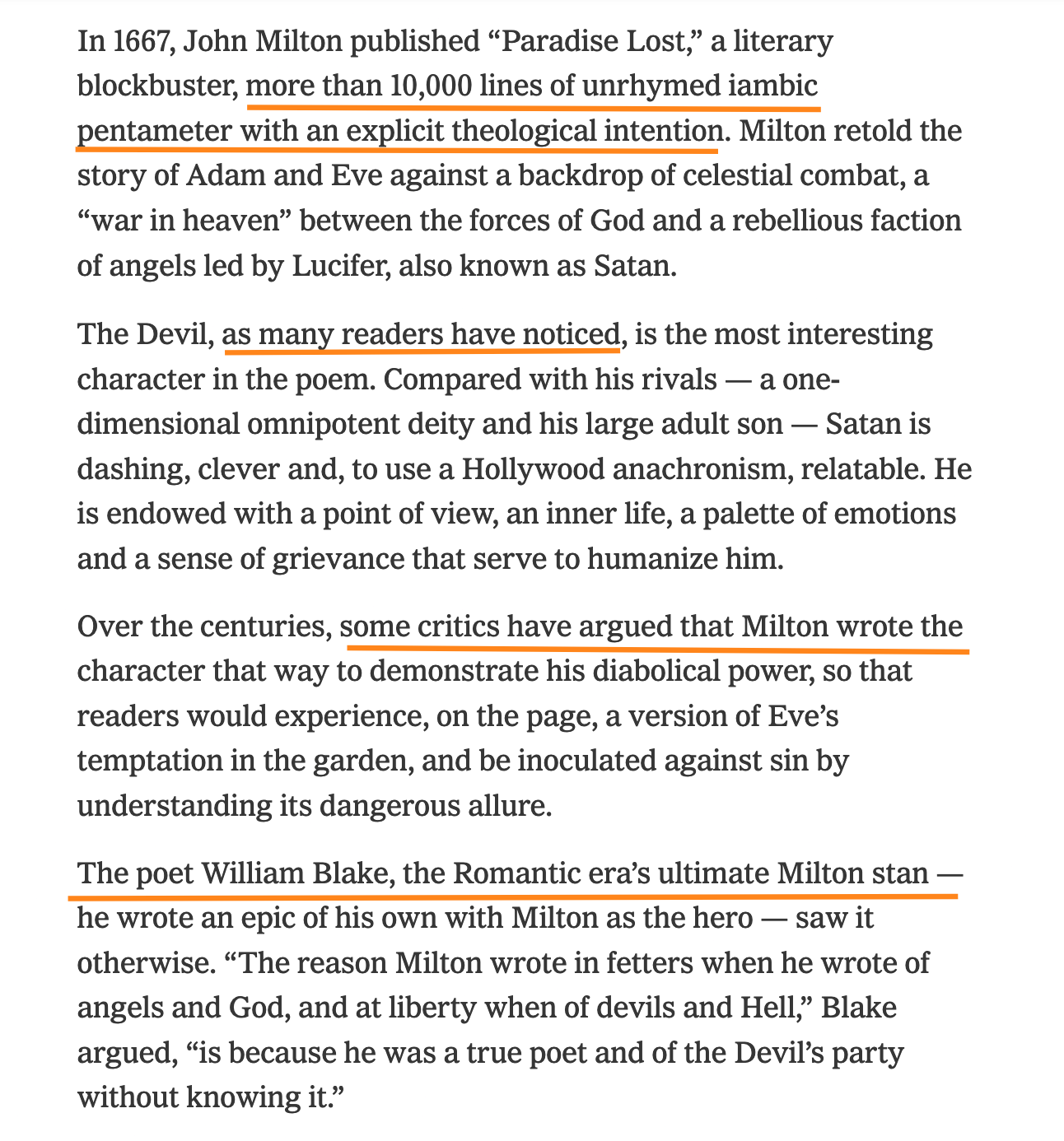

This is from a very weird piece A.O. Scott wrote recently about the resurgence of “villains.” It is weird because… Scott sort of admits immediately that there is no such resurgence! But then continues forward anyway.

What matters here, for my purposes, is:

these paragraphs appear to be written with the idea that there might be a person out there who doesn’t know who John Milton is or what Paradise Lost is (more than likely, really) and, in not knowing these things, really needs to know that the poem was important (“blockbuster”) and also, for some reason, that it’s ten thousand lines of unrhymed iambic pentameter;

there is absolutely no need to summon the specter of “many readers” who think the Devil is interesting—you can actually just say “the Devil is the most interesting character person in the poem”—you would be wrong (it’s Eve) but “most interesting” is not a category you need a poll to prove;

more to the point, you don’t need to bring in “many readers” when you have the reader, William Blake, nor do you need “some critics” (who?) to be a foil to Blake, you can just say “the devil is the best.”

There is also, again, the normal low / high bounce that everybody likes to do (me included)—large adult son, stan, etc. But while I might be prone to get cranky about these in another context, here I regard them with positive affection because they feel like vestigial traces of an authorial voice. The screenshot above is what happens when a relatively simple thought gets fed through a certain kind of machine. These are all the things you have to do to be able to express the basic thought “Milton, who presumably did not care for the devil, wrote a poem in which the devil was the most interesting and sympathetic person. As William Blake memorably said.…” etc etc etc.

I don’t pull this example out because I think A.O. Scott is a “bad writer,” but because I think he is not. I think he is a good writer working under impossible conditions, and it turns what could be a witty and provocative reflection on villains into a weird slog full of “many readers” and such. Because, after all, I’m not reading this article as a piece of reportage about what many readers and some critics think. I am reading it because I want to know… what A.O. Scott thinks about villains. But that’s exactly what I never get. I can read the whole piece (and have) without being able to tell you what he thinks.

What this all comes to—I believe—I mean, MANY READERS (my dogs) BELIEVE—is a refusal of authority.

Because I often stress qualities like humility and humor when thinking on here about writing, it probably seems odd to suddenly drag in authority like this. This is partly because I don’t regard Substack as a place to write “authoritatively,” but speculatively. It is a place for testing out ideas and for conversation and for following long-running interests to see what happens. If I drop a piece on here written the way I write other places, it won’t really work—I mean, I did, and it didn’t.

I’ll still do that from time to time, if I write something I like and it doesn’t get picked up, but every medium has styles that work best, and the best Substack style, for me, is what I think of as “horizontal.” I am making eye contact with you, you are making eye contact with me. We speak to each other.

Writing outside of Substack, on the other hand, I tend to get a little more high-handed, i.e., this piece on Miss America, which is probably a favorite piece of mine:

The Miss America Competition, which celebrated its 100th birthday this year, has now outlived key parties and manned missions to the moon, the VHS tape and the subway token, the Soviet Union and nitrate film. It outlives even itself, seeming to hang on more because the infrastructure remains in place than from anyone’s active desire to see it. And as last month’s streaming-only broadcast of the centennial pageant indicates, even inertia can get you only so far. People once watched Miss America on broadcast television, tens of millions of them; it was an institution of enough consequence to be worth protesting, as many did. But who needs a pageant these days? If you want to watch women strain to meet an ideal of femininity no person actually desires, you watch “The Bachelor.”

But that piece existed in a certain context that let it be arch in this way. And while I read quite a bit about and around Miss America for that article—I read American Pastoral!—you will notice I don’t drag much of it in. It’s necessary reading for me… but not really for you. (Well, American Pastoral is really good.) And if I had written the more defensive version of this where I did cite some study or another, the Miss America fans still would have gotten mad at me, but I would have liked the piece less.

However, more to the point, the All Horned Up book I’ve created doesn’t inhabit a speculative tone either—not even a faux speculative tone! It is just bringing in props it feels it needs. But that’s not how you establish authority. You either have it because of something you know, an expertise you possess etc, or you have it because you are willing to take it (along with the responsibilities authority confers). You assert you have it, and the rest follows. (Or doesn’t, in the case that you are catastrophically wrong about unicorns.) Another way of putting it: there are ways of writing where you very carefully avoid being wrong. But this is different from being right, or even from saying something such that you could be right or wrong in the first place.

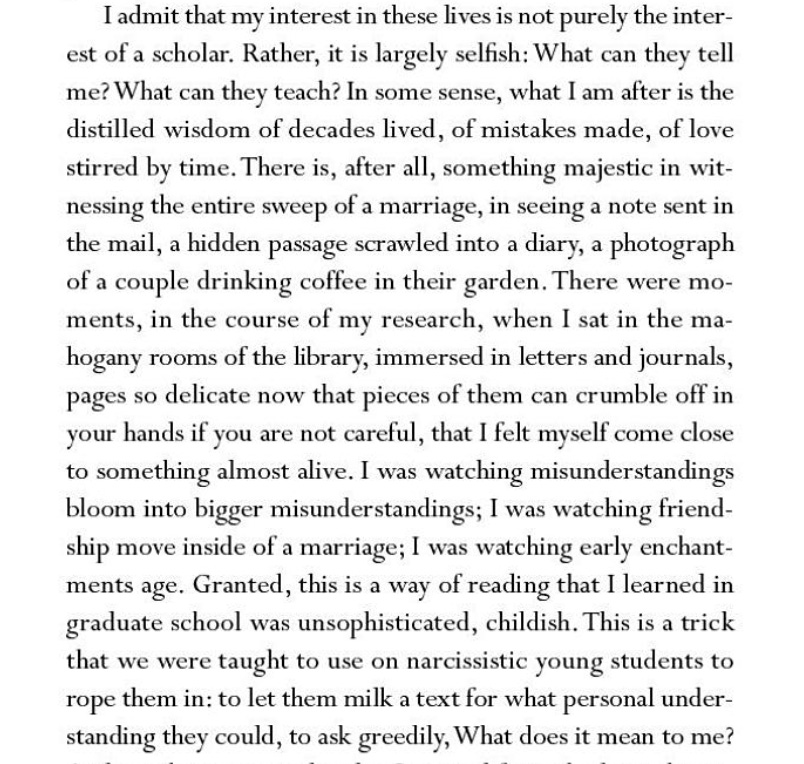

OK, pivot. Let’s talk about a real book now. Here’s the opening to the introduction of one of the books that is in the personal BDM canon, and perhaps yours too—Phyllis Rose’s Parallel Lives: Five Victorian Marriages (1983):

When Leslie Stephen, the Victorian man of letters, read Froude’s biography of Carlyle in the early 1880s, he was shocked—as were many people—by its portrait of the Carlyles’ marriage. He asked himself if he had treated his wife as badly as it seemed to him that Thomas Carlyle had treated Jane. With the Carlyles in his mind, Stephen, after his wife’s death, enshrined his self-exoneration in a lugubrious record of his domestic life which posterity has dubbed The Mausoleum Book and I, reading it, conceived the idea for this book. Froude’s life of Carlyle is a masterpiece, but much biography shares its power to inspire comparison. Have I lived that way? Do I want to live that way? Could I make myself live that way if I wanted to? Nineteenth-century Englishmen read Plutarch’s Parallel Lives of the Greeks and Romans to learn about the perils and pitfalls of public life, but it occurred to me that there was no equivalent or even vaguely similar series of domestic portraits.

So this book began with a desire to tell the stories of some marriages as unsentimentally as possible, with attention to the shifting tides of power between a man and a woman joined, presumably, for life. My purposes were partly feminist (since marriage is so often the context within which a woman works out her destiny, it has always been an object of feminist scrutiny) and partly, in ways I shall explain, literary.1

Here, we have a kind of “cold open”—Leslie Stephen’s reflexive self-condemnation—which brings Rose in as a character. It establishes the ways in which we’re often reading biography as a series of alternately cautionary and instructive tales: Rose reads Stephen reading Froude “reading” Carlyle (sort of). Then Rose lays out her goals and her angle. While Rose does introduce Stephen as a “Victorian man of letters,” I think this is necessary for two reasons. First, Stephen is a more obscure figure; second, it is a easy way of placing us in the time (Victorian) and context (letters) in which she plans to deal.

What she isn’t doing is hiding. Parallel Lives is a book primarily about other people, and I couldn’t really tell you a thing about Phyllis Rose herself, but what we get throughout is her analysis, her conclusions, and her opinions. This book is her house; she is master here. She establishes this from line one.

Let’s have another example of a writer who successfully conjures up “authority.” Here’s the opening of the first chapter of a book I’m currently reading, Garry Wills’s Nixon Agonistes (1970):

February 1968: It is early morning in Wisconsin, in Appleton, air heavy with the rot of wood pulp. This is the place where Joe McCarthy lived and was buried—a place, once, for Nixon to seek out on campaign; then, for a longer time, a place to steer shy of. He has outlived both times, partially. And it is too late to care in any event: the entire American topography is either graveyard, for him, or minefield—ground he must walk delicately, revenant amid the tombstones, whistling in histrionic unconcern.

This opening is worth singling out not only because it’s great, but because it was originally for a magazine, and you can tell if you look at its compression and then back up at Rose’s more leisurely, multi-layered unfolding. (Nixon Agonistes is a pretty long book and much of it is not this highly compressed.) Wills has one theme he wants to hit in this paragraph and it’s DEAD. Not even “death”—that implies a transition from life—DEAD. Rotting wood, dead Joe McCarthy, revenant Nixon. Dead, dead, dead. This is Nixon’s situation. Dead. Wills has an opinion on every single person he encounters throughout the book and he delivers all of them without qualification (“Henry Kissinger, who looks like a serious Harpo Marx”).

Both these examples—Rose and Wills—are old, obviously. There is a lot in Nixon Agonistes an editor would no doubt kibosh now (like its epigraphs in untranslated Latin, or, well, the title). The reason to pull them out is because they are both heavily-researched works and, in Wills’s case, involve a lot of what you could call “vibes-based cultural commentary,” such as when he goes to the Democratic National Convention in Chicago and offers his opinions on the left-wing student protestors and the liberal finger-waggers freely. But when a bigger name is brought in, when a reversion to the first person and subjective is called for, these never obscure Wills’s own direction of the show. The work that goes into these books is dissolved, synthesized, submerged.

Here is one final example of a writer who is not afraid of her own authority—the opening of Molly McCully Brown’s Places I’ve Taken My Body (2020), an essay collection about her life with cerebral palsy (which I really liked):

For the last six months or so, whenever I’ve moved suddenly—stood up out of a chair, bent down to get my laundry from the machine, sneezed too hard in line at the convenience store up the block from my apartment—my back has spasmed, as if someone’s making a quick, hard fist around my spine and squeezing. At first, it was just a twinge, enough to startle me. These days, it knocks me off balance if I don’t brace for it first. And so I stretch more, and I stand and count to three before I step, or carry my coffee cup away from the table, or crouch down to put the dishes in the cabinet. I turn off the fan in the bedroom while I sleep, though it’s May in Mississippi and already eighty degrees. Better to wake up sweating than knotted and tremoring from some little chill.

They’re tiny, these adaptations. I suspect it took me months to notice I was making them. My life is built to flex unconsciously around new pain. I couldn’t even tell you what I used to do with the small space the spasms fill. This version of my life erases the last one, like a tape someone’s recorded over. Already, my memories begin reworking themselves to admit the spasms’ brief delay: two seconds tacked on to the end of everything, a touch more hurt.

I wanted to use this book because it is 1) pure memoir and 2) not a big acknowledged great book, like the other two and finally 3) recent. I love memoir and would hate for it to seem like I have some beef against the first person. But Brown is indisputably the only authority possible on her subject—how it feels to live in her body—and she acts like it. The authority she assumes here exists in contradistinction to her lack of physical control, her inability to exercise authority over her memory’s adjustments.

But Brown is, also, chatty and informal. Authority doesn’t have to mean you sound like you’re speaking from the top of a mountain (or the bottom of a library). It just tells me: this writer is in charge here. She has things to say. There are more examples I could use, and I’m aware the three examples I picked are limited in various ways (all Americans, for one) but I think these three all show what I mean in different registers and styles.

Writing—even critical writing of the kind I usually do, which I often (though neutrally!) describe as “parasitical”—creates a world of sorts. You can imagine this metaphorically in various ways: as a house, as a theme park ride, as a dance, as a series of time lapse photos, and so on. Pieces have a tempo, they have drama, they have plot. You, the writer, are the master of ceremonies. You decide what happens, what goes where, when people see it, and how. Nobody else is in charge. It is just you. When you read a piece of writing that is genuinely great (or even simply, good), that is what you sense: that the person behind this has accepted their authority and the responsibility that comes with it. If the windows leak, if the time lapse is out of order, if the ride leaves people stuck at the top of the Ferris Wheel—that is one person’s fault. Yours.

Really excellent non-fiction writing is often collaborative—that is, the writer has a trusted reader or critic or editor with whom they work. You do not build the house alone. Nevertheless, the buck has to stop with somebody. It ought to stop with you.

Parallel Lives is such a good book, in such a straightforward and sturdy way, that it inspires fairly direct imitations, one of which I think is instructive to look at here: Katie Roiphe’s Uncommon Arrangements, which is essentially Parallel Lives but for Bloomsbury. While I know many people find Roiphe (at best) grating vis-a-vis her writing “persona,” the idea behind Uncommon Arrangements is really good, and in theory she should have done a great job with it. But actually, in my opinion, she only does an okay job with it.

If you go look at the introduction to Uncommon Arrangements, you’ll find that it basically mimics the opening beats of the introduction to Parallel Lives. The third paragraph is when it starts to diverge. Rose puts out a statement of belief:

I believe, first of all, that living is an act of creativity and that, at certain moments of our lives, our creative imaginations are more conspicuously demanded than at others. At certain moments, the need to decide upon the story of our own lives becomes particularly pressing—when we choose a mate, for example, or embark upon a career. Decisions like that make sense, retroactively, of the past and project a meaning onto the future, knit past and future together, and create, suspended between the two, the present. Questions we have all asked of ourselves such as Why am I doing this? or the even more basic What am I doing? suggest the way in which living forces us to look for and forces us to find a design within the primal stew of data which is our daily experience.…

Roiphe becomes subjective and self-deprecating:

Even here, again, I see the basic reason I prefer Rose’s introduction is that she doesn’t disavow her own authority. Her book is, in the end, much more coherent. But I think it’s also sort of interesting that Roiphe cannot get to where she wants to go without insulting herself. And the big problem with Uncommon Arrangements, I thought back when I read it, is that Roiphe absolutely cannot make up her mind about what she thinks about the people she’s writing about. She doesn’t want to be square and condemn them, but she also wants to preserve the moralist tendency of Rose’s book and give a “lesson” (but often, the “lesson” for her is, these people were miserable).

A comment on Willis' phrase "in Appleton, air heavy with the rot of wood pulp." -- I grew up across the river from the pulp mill that gave the air that smell, and it's fair to say both that the phrase is evocative of the morning air back then, and, strictly speaking, incorrect. The smell came from the chemical reactions involved in breaking down wood into pulp, and managed to suggest something rotting while still smelling quite unique and utterly offensive. The smell of the air on my walk to school depended on which direction the wind was blowing, either from the pulp mill or the milk condensery further down the river (which smelled of sour milk). The condensery was a little bit better than the pulp mill.

Both the pulp mill and the milk condensery are gone now, and the river running through Appleton is cleaner, with bald eagles, cormorants, and pelicans frequenting it in the summer. A bust of Joe McCarthy, which was still prominently displayed in the Outagamie County Courthouse entry as late as 1981, has also been hidden away.

When I read the All Horned Up paragraphs, I thought its structure was very like my old 12-page typed college research papers which were due at 9 am and that I began at 7 pm the night before. If I was the same dumb-ass college kid today I’m sure I’d use ChatGPT, which has the same weird unauthoritative discursive style.