say to yourself: this and that it is in me to do, and I will do it!

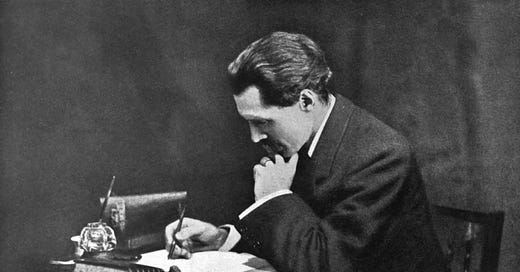

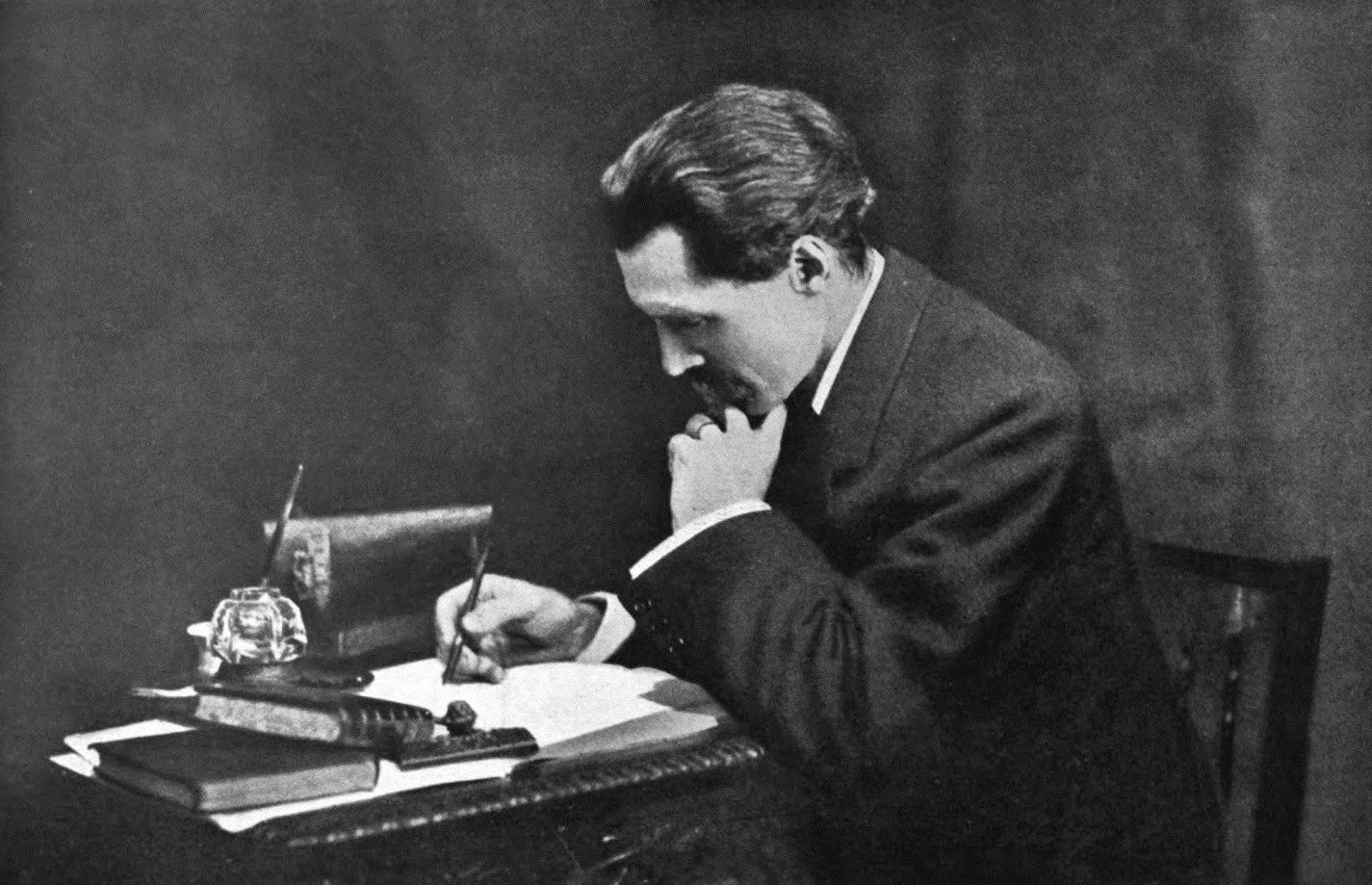

the odd women (george gissing, 1893)

For years, the main distinction that George Gissing’s book The Odd Women possessed, vis-a-vis myself, was that it was one of the first books I can remember deliberately not finishing (as opposed to forgetting to finish it, which happens all the time). I found something about Gissing’s descriptions of people, what they looked like, very off-putting.1 But I did look up how it ended at the time and was interested to see it makes the short list of what I consider a canon of refusal: books in which a woman is offered love and marriage from a sympathetic man and says no.2

This kind of ending is rarer than you might think. The Princess of Cleves (1678) ends this way, as does Letters from a Peruvian Woman (1747)—those two classics to be found on every girl’s nightstand, I’m sure—and probably something else does but I can’t think of it right now.

The gender-flipped version of this ending (man renounces woman) is much more normal—thanks ma’am but I reckon I cain’t be domestickated I ain’t yet ready to hang up these spurs hi ho Silver—usually because man renounces woman in favor of a higher cause, pursuing greatness over a domestic happiness (in which he knows he wouldn’t really be happy, so in fact he is just doing what he wants, I suppose, but the long way around). The trouble is that women in classic, tending-toward-marriage sorts of novels rarely have something to renounce men for, except the principle of doing so; they are, to riff off George Eliot, foundresses of nothing.

So I was always saying to myself, “you should really go back to The Odd Women… sometime…” and the existence of a new edition from Smith & Taylor Classics provided an excuse to finally do so. But I did not read the Smith & Taylor edition—because it is not, at this time, out—I read the version one can acquire from Project Gutenberg.3 Would it perhaps have been better to wait and read that edition with its scholarly apparatus, its introductions, and so on? Well, yes, now that you say it, but I didn’t.

The opening chapter of The Odd Women forms a kind of prelude to all that follows, as Elkanah Madden, a doctor, a widower of two years, looks over his six daughters and vaguely plans to make financial provisions for their future starting tomorrow. His daughters, who are educated “in every proper direction,” are, naturally, being brought up to no particular employment; for “the thought…of his girls having to work for money was so utterly repulsive to him that he could never seriously dwell upon it.”

Unfortunately for Dr. Madden and his daughters, he dies in an accident that night. The six girls are flung upon their own devices—which are not much. In the sixteen years that pass between chapters one and two, three of them die. The two older girls, Virginia and Alice, end up as a lady’s companion4 and a governess respectively; the youngest, Monica, works in a shop. Chance causes them to reconnect with another character from chapter one—Rhoda Nunn, then fifteen, now in her thirties. Rhoda, who was brought up to work, has, in concert with Mary Barfoot, an older, wealthier woman, set up a school that helps train nice girls for careers by teaching them typing and other office skills, rather than the poorly paid “respectable” domestic jobs they could otherwise get. Rhoda can tell at a glance that it’s much too late to do anything with Virginia and Alice, but Monica might be salvagable for her purposes.

In certain ways The Odd Women is curiously like Henry James’s The Bostonians in its set-up—both in its cast of feminist idealogues and also because Miss Barfoot’s no-good wastrel cousin, Everard, starts dropping by. However, instead of having any interest in Monica, the book’s analogue to Verena, Everard decides it would be fun to seduce Rhoda (then falls in love with her for real). They engage in a battle of wills throughout the book that conclude first in Everard offering Rhoda a marriage in all but name (i.e., they will live together). She refuses and demands marriage. He capitulates and regrets it. They “break up” (as it were) when circumstances intervene to cast doubt on Everard’s character; when they are reunited, the situation is reversed. Now Rhoda wants to live together without marriage but Everard balks.5

In truth (as the reader in fact knows) he never really wanted that outcome, he just wanted Rhoda to agree to it as a test of her devotion to him. Flatly rejected by Rhoda, Everard marries an accomplished and wealthy girl of his own social class.

Meanwhile, the situation of the three Madden sisters continues to deteriorate; one becomes an alcoholic, one continues to work as a governess, and Monica, terrified of becoming her sisters, marries a wealthy older man who proposes to her. “I can’t be contented with this life,” she tells a friend. “It seems to me that it would be dreadful, dreadful, to live one’s life alone.… Whenever I think of Alice and Virginia, I am frightened; I had rather, oh, far rather, kill myself than live such a life at their age.6 You can’t imagine how miserable they are, really.” The man she marries (with the incredible last name of Widdowson) turns out to be not only extremely boring but jealous and controlling. Monica, having lucked into what was meant to be her social “career,” that is, marriage, turns out to have sealed herself in a tomb.

One of the more interesting quirks of The Odd Women is that practically everybody in it hates women, but Rhoda Nunn is such a misogynist, has such an intense hatred of other women for the greater part of the book, that it becomes a little improbable that she has also dedicated her life to improving their situation. At one point Everard Barfoot asks her if she would approve if he beat his irritating sister-in-law; Nunn replies “I think many women deserve to be beaten, and ought to be beaten.” There is general recognition in the main cast of characters that women are not really human beings, for the most part; they are something lesser which can perhaps be made into human beings in a few generations.7 Rhoda’s dedication to teaching girls from good families to work is partly because some large remnant of them will never find marriage (those are the titular “odd women”), not out of lack of personal charm but rather because there are many more women than there are men. But it is also because she and Miss Barfoot understand that without work there can be no equality. “I am not chiefly anxious that you should earn money,” Barfoot tells her girls, “but that women in general shall become rational and responsible human beings.”

Everard, who does not work (he lives off of income generated by his inheritance), finds this all sort of amusing but clearly does not take it very seriously. When Rhoda protests to him that she cannot “abandon” her work, Everard asks: “What is your work? Copying with a type-machine, and teaching others to do the same—isn’t that it?” In the brief period in which they could be said to be engaged, he broods:

Barfoot, over his cigar and glass of whisky at the hotel, fell into a mood of chagrin. The woman he loved would be his, and there was matter enough for ardent imagination in the indulgence of that thought; but his temper disturbed him. After all, he had not triumphed.…

She had great qualities; but was there not much in her that he must subdue, reform, if they were really to spend their lives together? Her energy of domination perhaps excelled his. Such a woman might be unable to concede him the liberty in marriage which theoretically she granted to be just. Perhaps she would torment him with restless jealousies, suspecting on every trivial occasion an infringement of her right. From that point of view it would have been far wiser to persist in rejecting legal marriage, that her dependence upon him might be more complete.

Everard, despite his apparent interest in Rhoda for her high idealism, is not really so different from Widdowson (who also is drawn to Monica for what he perceives as her unconventionality, but desires her to be submissive and conventional after marriage). What Rhoda comes to understand before she decisively rejects Everard is that whatever relationship they enter into, she cannot trust him to keep up his end of it. This lack of trust is not about sexual fidelity but something deeper; she knows Everard, ultimately, is not on her side. The social world in which they operate will see to it that their marriage (or quasi-marriage) becomes like any other marriage. “You have spoilt my life, you know,” she tells Everard during their brief engagement. “Such a grand life it might have been. Why did you come and interfere with me?” But by the end of the book she has righted the course; her life is unspoilt. It may even be grand.

As a work of social commentary I think it is fair to say The Odd Women has aged unevenly.8 As a legal and social institution, “marriage” today is just not what it was; a woman in Rhoda’s position does not have to choose among sexual fulfillment, a life lived independently, and having a good name. If somebody operates under marriage-or-nothing terms these days they do so on a strictly opt-in basis. The scandalous musing of one charcter—that in the future perhaps people will be able to divorce for no reason except wanting to—is just how things are. I can certainly see why I didn’t finish it when I tried to read it back in the day. Though at the same time, I can remember how bitterly I resented the ending of Middlemarch at that age (in which Dorothea chooses happiness over greatness), and I might have worked my way around to fondness for The Odd Women if I’d actually got to the end.9

On the other hand, I read it because I am finding the conversation around “gender war” of late, particularly after the election, even from people whose work I otherwise like, intensely irritating (sorry, people whose work I otherwise like). I have seen such an outpouring of opinion that it would be wrong for American women to do a version of South Korea’s separatist “4B” movement that I start to think maybe it would be a good idea as otherwise I do not know what to make of such a sweeping resistance to a thing I am confident nobody is doing.10 And what I see as Rhoda’s fundamental problem—that Everard expects her to be on his side, but is not reciprocally on her own—does have emotional resonance, even if its social context has changed. In refusing to marry Everard Rhoda rejects a poisoned gift. To have love on those terms would be intolerable, but they are also the only terms she’ll ever have. So she doesn’t.11

Over twenty years ago, there was an infamous New York Times article that came out called “The Opt-Out Revolution.”12 The gist of it was that the reporter, Lisa Belkin, interviewed various well-credentialed women who were all in the same book club who were dropping out of the workforce after having children. (Later, they dropped back in.) “I don’t want to be famous; I don’t want to conquer the world,” said one; “I don’t want to be on the fast track leading to a partnership at a prestigious law firm,” said another. If working is making your life harder and you, in some sense, don’t “have” to do it—you have a husband with a fat enough paycheck that you can leave—then why do it? Work is bad, we all hate work, etc. Right…? Do you really, in your heart of hearts, want to spend your hours on earth “workin’ on a / pharmaceutical company’s merger with / another pharmaceutical company”?

No, you don’t, nobody does, that kind of tedious white collar work sucks and we all know it. Women are actually too smart to fall for this trap (goes the article) they’re actually just doing cost–benefit analysis and realizing they want to have fulfilling lives instead of lucrative ones. It’s too bad that somehow this isn’t possible for men yet there you have it. Men are just so dumb, they somehow end up with all the wages.… This is not my point of view, just to make it clear, it’s the article’s point of view that women don’t “run the world” because “they don’t want to.”

Now to be clear, whether or not any individual woman should be a homemaker is not my business, or even what I’m talking about here really. Do what you want!13 Whether or not future BDM, who has no doubt created BDM Jr. through the first documented case of human parthenogenesis, should raise her BDMling as a stay-at-home mom is not even my business (it’s her business). I’m mentioning the article because this is all what The Odd Women is about—the importance of working when you do not technically have to, the struggle to articulate that work is about money but it is not only about money, it is also about adulthood.14

For the hyper-ambitious women profiled here, work is purely about status and they do not know how to explain its value (or lack thereof) in terms of independence and self-respect.15 They feel their children are more important than their work (probably true!), that in the grand scheme of things one more lawyer doesn’t matter (also probably true!), and so on.16 In other words, their pull toward domestic life is because of deep sense of their own unimportance—they can disappear, nobody will miss them, it’s fine. That it is true that being a mother is more important than being a lawyer does not alter 1) that nobody acts like that’s true and 2) the question of whether or not without a job somebody can stand on their own two feet and face the world secure in their sense of self-worth. Some people can, of course! I know many. Some people can’t.

But I’m so tired, so tired, of people who tsk-tsk any expression of even negative emotion—don’t make mean jokes (they might alienate people), don’t preach independence (what are you, a girlboss?), don’t stand up for yourself (hush, HR lady), don’t have a sense you can take care of yourself (that’s toxic individualism). Don’t learn you have teeth and that you can bite and that if you make people angry at you you’ll live. I’m sorry, but this is such a stupid conversation, it’s being conducted in stupid terms. If George Gissing could grasp the dynamics here in 1893, what’s your excuse? Please.

Marks one of the only times I can remember somebody’s earlobe being singled out for attention. For years afterward my main association with The Odd Women was earlobes. “Isn’t that the earlobe book” I’d think seeing it on my shelf.

Actually, I misremembered this and / or the summary was done badly—it’s a bit more complicated than that.

However, I’m sure the Smith and Taylor edition is much nicer, so if you yourself want to read it, consider picking it up.

One of those jobs you don’t seem to be able to get nowadays.…

There are certain aspects of the Rhoda Nunn–Everard Barfoot relationship that strongly echo Harriet Vane from the Dorothy Sayers mystery books; in particular, living together without marriage only for that to turn out to be a “test” is I think the situation between Harriet and her (dead) lover in Strong Poison.…

(They are in their thirties.)

By the end of the book I think Rhoda has softened slightly.

The prevalence of last names that whack you over the head with their double meanings (Nunn, Widdowson, Madden) can be a bit much.

“George Eliot never ended her books properly. There’s so little for heroines to do; they can fall in love, they can die. As the story begins, you wonder whether the heroine will be happy, but by the middle of it you’re beginning to wonder if she will be good. Such is George Eliot’s sleight-of-hand, i.e. cheating.” (Joanna Russ, On Strike Against God)

Real ones await the revival of Cell 16.

The choice isn’t really greatness or happiness because Rhoda knows that she will not be happy. This is one reason I have come around to the ending of Middlemarch.

When I re-read this article I realized I had manufactured several quotes from it seemingly out of thin air—I mean not quotes in anything I wrote just quotes in my head.

I would only say, don’t be one of those TikTok stay at home girlfriends—set yourself up for an alimony check if things go south. That goes for you too, boys! You can get alimony too!

I am unemployed.

Rhoda and Miss Barfoot are pointedly uninterested in helping the working classes better themselves, which is wrong of them, but one could reasonably point out that nobody needs to teach the working classes how to work—it’s only women who were brought up with certain assumptions who need to be taught how to take care of themselves.

Also from On Strike Against God: “Why did Ellen forget the classic exchange? I mean the one where they say But aren’t you for human liberation? and you say Women’s liberation is for women, not men, and they say You’re selfish. First you have to liberate the children (because they’re the future) and then you have to liberate the men (because they’ve been so deformed by the system) and then if there’s any liberation left you can take it into the kitchen and eat it.”

|"They are in their 30s"

oh yeah i definitely get it

Oh yeah! I was thinking of Strong Poison re: books that end with the woman choosing not-marriage, though it's sort of undone by Gaudy Night (by no means to my chagrin).

Feel like there are a couple Barbara Pym books that also fit this mould, though perhaps that goes without saying [speaking to "femcel canon" phrase coiner... my friend independently came up with "spinster lit"].

Have you read (... why do I ask; she hates answering this) A Suitable Boy? I remember being shocked & scandalized by the ending, i.e. Lata's choice of a husband, as a teen (it seemed like the death of hope), but when I re-read it in my mid-20s I thought the protagonist had just been wiser about life than I had been at 17.