When it comes to discussing a “canon” or “canonical works,” usually one is doing one of two things:

saying you have a list that is, in some sense, the best of the best;

saying you have a list of things one ought to have read to be an educated person, either in general or in a specific area.

The lists you produce for each type of book will probably have a substantial amount of overlap. Still, they are not the same thing. It is worth differentiating them because the second definition, circular as it gets, is useful for explaining what people ought to be taught and not left to find on their own.

To give an example: suppose you think Mary Shelley’s Matilda is a novel that is much, much superior to Frankenstein. If you had to go before some weird high council of curricula, let’s say it’s a bunch of Martians who want to be caught up to speed, it would still be crazy to suggest Matilda over Frankenstein. That is because Frankenstein is a massively influential book that is credited with starting an entire genre of fiction, and Matilda is not. Frankenstein is a text that subsequent books are “in conversation” with, and Matilda is not. But this isn’t a literary judgment. Maybe Matilda really is a better book. (I haven’t read it.) The argument that Matilda is a better book, however, will be best pursued in a world of shared realities.

Thus the answer for why schools should teach the Odyssey is that… people should know what the Odyssey is. It’s circular! But it’s true. You should know this, because you should know it. There are lots and lots of great works of art in the world, and if you leave your high school experience familiar with the canon, you will be better equipped to appreciate all of those things. If schools produce graduates out of touch with their cultural heritage, those schools are failing those graduates.

But they have been failing them for a pretty long time. It’s not really my intention to turn this newsletter into the John Milton Sideshow Quarterly, but one memory that sticks with me from my high school–aged years was sitting in, as a prospective student, on a class about Paradise Lost at a small liberal arts college and hearing every single person in the room, the professor included, fail to use the term “original sin” correctly. And much as it pains me to make this argument about something I actually do believe in, the reason to know what things mean in Christianity is that Christianity has been, let’s say, historically important, and when you read these texts, they are dealing in meanings and presuming knowledge.1

Now there are two big problems with the circular definition of the canon as “stuff that’s important because it’s important.” Number one, this is essentially how the canon ends up racist and sexist and so on. (Whereas a canon of the best of the best is being judged by a different criteria, and is, in theory, egalitarian to all producers of excellence.) It is easy to cut things out of lineages of influence, even if they actually were influential, unless you are dealing with a juggernaut like Frankenstein.

Number two, though, is that, like all circular statements, it begs2 a question. I can keep saying it’s important for things from the past to be legible to you.… but what if you simply respond: I don’t give a shit about the past? What’s the answer there? Is there one?

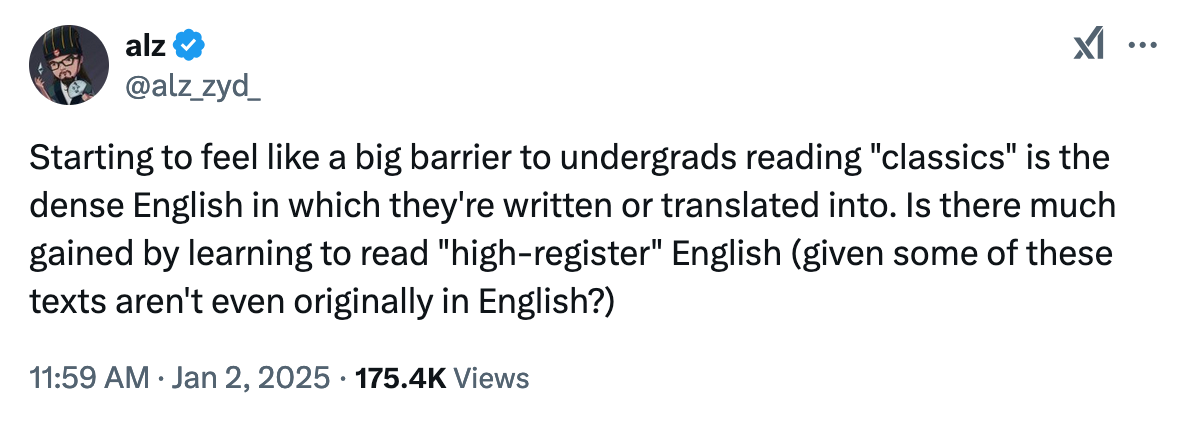

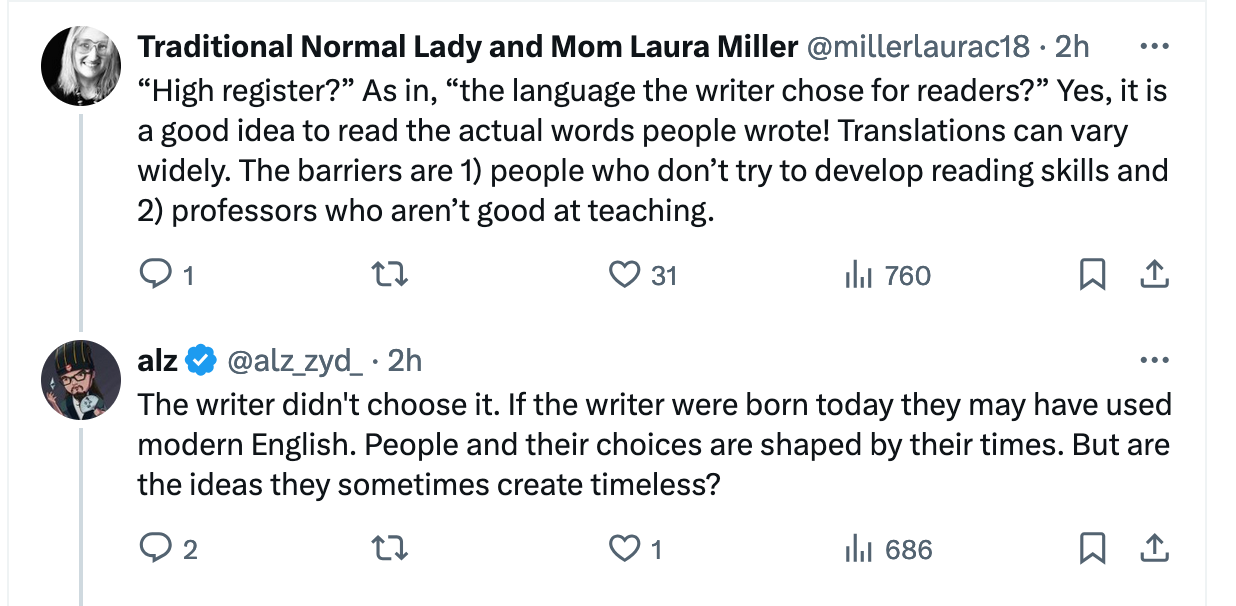

Yes, I saw a tweet and it made me mad. (You can see this genre of piece listed under “culture writing”: “a thinkpiece about a tweet you read.” See, I’m a culture writer.) Here it is.

This is obviously cousin to the really stupid “it’s unfair to think people should know what the Odyssey is” discourse that my friend

skewered recently here. Actually, if I had to guess its lineage, this tweet exists because “it’s unfair to expect people to know what the Odyssey is” became “do not read Emily Wilson’s woke Odyssey because it doesn’t sound epic enough,” which perhaps gave rise to this guy saying this thing.Translation is one thing and in a certain sense, all this guy is doing is explaining, in the stupidest way possible, why we will continue to need “new” translations. But his argument is more expansive than this and encompasses basically anything old:

I genuinely don’t know how one responds to this because I don’t know how to argue that it’s good to care about “history” or “language.” I feel like I’ve walked into a glass door. I have no idea what you do to convince somebody with such a basic lack of curiosity, whose relationship to knowledge is purely about speed and consumption, that they’re wrong. I really don’t! Or at least I don’t without going back to the circular argument again, that you should care because you should care.

There are some things that I think you only learn the value of through doing them—exercise, prayer, and so on. The practice teaches you the value of the practice. This is certainly true of reading, too. Reading and having read are qualitatively different from getting the highlights from somebody else. In some cases, that qualitative difference may be pretty minimal; in others, it will be huge.

And for that reason, years ago I decided to give up on arguments like this one because in the end it felt pointless. You should just do it, and you will attract people. But then when I read this kind of thing I feel a real sense of the void.

Something which is true of exercise and true of reading, I think, is that people actually like difficulty. They like it when things are hard. That is why people like playing video games that seem to be primarily about wiping out over and over, like Elden Ring. While everybody understands that a game like Elden Ring coexists easily with Stardew Valley in somebody’s library, nobody asks why people make games that are hard.3 They do it because tackling challenges, feeling your abilities expand, and making progress is fun.

Is a problem, essentially, that we’ve kind of forgotten that it’s good for things to be difficult, because difficult things present challenges that can be overcome? Maybe this is just another way of punting the question of “why care.” And… a book is not a game in various important ways (you do not “beat” books). But feeling something that was very hard get easier is one of the best feelings you can have. I feel like a world in which you just have everything summarized and predigested for you is a world in which you never have that feeling. That’s still not a response, I guess.

Furthermore, it’s useful to know when what you’re reading is actually diverging from a consensus, i.e., Milton is an Arian.

and it does BEG that question, I believe… it will be embarrassing if I get this one wrong

By “nobody,” I don’t mean people in the games industry; I’m sure there are game execs who are trying to figure out “Elden Ring but easy.”

OK, now it's just starting to feel like you're messing with me - first giving me an Appleton reference, now talking about translations of the Odyssey when I've got a PhD in Classics . . .

I have indulged my interests in ancient thought and literature to an unhealthy degree, but it has given me a sense of what we're arguing about when we're arguing about a canon. The place to start is to recognize that we are talking about social phenomena, that for there to be "classics" and a "canon" there needs to be a community of people who are playing a game that we can call "culture".

If we're using the Odyssey as an example, we're talking about a poem that has belonged to several different cultures. In the earliest culture we know of to which the Odyssey belonged, the Odyssey was recited in its entirety at religious festivals by specialists called rhapsodes. These performances were mass media, in that the rhapsodes performed before crowds, and they were popular media, in that the performances were something that people attended for their enjoyment, rather than as a duty. The performances of the Odyssey (and the Iliad, often at the same festival) were so popular that some of the earliest poems composed as writing were poems that filled in the gaps in the story of the Trojan War and the return of the Greek heroes. At that point, the Iliad and Odyssey were classics in the same way that the movies "Sleeping Beauty" and "Star Wars" are for us - you'd been attending performances for as long as you could remember, and making references to them and reciting dialogue were ways to talk to other people with the knowledge that they would definitely get the reference.

None of us have any problem with classics in that sense. It may be the case that in the future, some of the classics will be forgotten and replaced by others, but that's just the way that mass or popular culture works. There are occasionally disputes at the boundaries over whether something ought to be classic in this sense, and a lot of Taylor Swift discourse fits here - those of us who aren't interested in listening to Taylor Swift need to figure out how much we need to know about Swift's work in order to get along with the Swifties in our lives. But no one is going to say that Swift's problem is that she hasn't made her work accessible enough. And in Ancient Greece, no one said that Homer wasn't accessible enough.

The problem that the post is discussing, however, is that some of the cultures that consider the Odyssey a classic, and part of a canon, are elitist, designed to exclude people from participating. If you find yourself being introduced to these cultures (and a liberal arts education is, at the least, an introduction to these cultures) you are put in the position of asking yourself - how much work do I really want to put into reading the books I need to read to fully participate in this or that elite, literary culture?

There are no good answers to this question. The nicest literary elite culture I ever participated in was the Greek Lyric poetry panels at academic conferences for classicists. The barrier to entry was high, but the stakes were low, and everyone was pleased as hell to meet other people who had the ability to say interesting, true things about poets like Pindar and Simonides. Just a very pleasant experience. At the same conferences, the worst panels to attend were always the ones on Greek Tragedy. Same barrier to entry, but because the tragedies are taught to people who don't know Greek, there is a bigger payoff to being an academic expert on Sophocles. And so the scholars who are more ambitious come up with increasingly implausible readings of the texts, and generally give one a feeling that they are bullshitting and don't care that you know it.

I can read Latin and Greek, I can throw around philosophical terminology in German and French, and even some in Sanskrit and Chinese, but there are also a lot of books that are deservedly in the canon that I have not read. I think reading books in the canon just because they are in the canon is something that you may need to do to develop your skills as a reader, or a writer, or to fit in with the culture that you want to belong to, but in those situations, it will not be FUN to read those books, at all, because you're not reading them because you want to.

Moby-Dick is one of my favorite novels, but I read it because I was really fascinated by the whaling industry as a part of US history. The great thing about Moby-Dick as a reading experience is that if you want to know what it was like to hunt whales in the middle of the 19th century, Melville tells you, in detail, and in a way that gets you looking at the US and the world differently. But if you aren't interested in whale-fishing, reading that book has got to be a terrible slog. Tangentially it's about the modern world, and homosexuality, and racism, and God, and sin, but it addresses all of these subjects metaphorically, with one metaphor, which is whale-fishing. I love that book, but I'm not surprised it was a failure when he published it.

Again, there is nothing wrong with taking on difficult intellectual challenges for reasons that are hard to explain. My life is defined by such challenges and I have no regrets about that part of it. But there is the work of learning things, and there is the pleasure of reading things, and mastering a canon is learning things. Canon comes from a word that means measuring-rod, and the point of having one is to have a bunch of books that possess qualities we admire, so that other writers can read them, see how they work, and take those lessons into their own writing.

The reason Shakespeare is in the canon is because, if you want to write plays (and screenplays), it is worth making sense of the archaic language and seeing how he made those plays work so well that even today people can take parts of his plots and turn them into gripping dramas. You can learn those plays through simplified versions, such as movies, or modernized texts, or (as I did with Macbeth as a child) comic books. But in those cases, you are trusting that whoever produced the movie, or the modernized text, or the comic book, is as good a dramatist as Shakespeare was, and it is very unlikely that they are. For every great work, that's the case. If you want to really grasp the Odyssey, you're going to need to learn Greek, or you're not going to learn all the lessons Homer has to teach you.

Nevertheless, ars longa, vita brevis. You need to make decisions, so read what you like, work at what seems important, and remember that the nerdiest cultures (high barriers to entry, low social stakes) will always be the most fun to belong to.

This seems related to the time a friend of mine in grad school pointed out in class the beauty of a particular line in a poem. The professor laughed at him and said, “We are here to talk about ideas. If you want to talk about beauty, join a book club.”